Musa for Arabic

Musa for Arabic

The use of Musa script to write Arabic has several advantages over the traditional script (in addition to its universality). Most visible is the lack of dots: each letter has its own form. There is a full letter for hamza, a letter for the emphatic lam (as in the name Allah), and many of the special signs needed to make up for the deficiencies of traditional script, e.g. sukūn, madda and waṣla, are simply not needed at all: Musa script is much cleaner.

The term Standard Arabic includes both the Classical Arabic of the Qur'ān and Golden Age, and Modern Standard Arabic (the language people are taught to read and write in schools), but nobody speaks it as a native language. In contrast, the vernacular spoken dialects, which differ considerably from one another, are rarely written. But it is not the role of the script to favor one or the other: Musa script can be used to write any of them. What that means is that the dialects of Arabic, including Classical and Modern Standard, differ as much from each other when written in the Musa script as they already do in speech.

Unlike the traditional script, Musa script for Arabic is written from left to right. Otherwise, a straight one-for-one replacement of traditional letters by their Musa equivalents is a good first step in transliteration. Here's a table of equivalents (I use the apostrophe ' to represent hamza, the exclamation mark ! to represent !ayn, and the underdot to represent other emphatic consonants) :

| Traditional | Name | IPA | Trans. | Musa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ا | 'alif | aː | ā | |

| أ | (as chair) | ʔ | ' | |

| ب | bā' | b | b | |

| ت | tā' | t | t | |

| ث | thā' | θ | th | |

| ج | djīm | ʤ | dj | |

| (in Miṣr) | g | g | | |

| (in ash-Shām or al-Maghrib) | ʒ | zh | | |

| ح | ḥē' | ʜ | ḥ | |

| خ | khā' | x | kh | |

| د | dāl | d | d | |

| ذ | dhāl | ð | dh | |

| ر | rā' | r | rr | |

| ز | zāy | z | z | |

| س | sīn | s | s | |

| ش | shīn | ʃ | sh | |

| ص | ṣād | sˁ | ṣ | () |

| ض | ḍād | dˁ | ḍ | () |

| ط | ṭā' | tˁ | ṭ | () |

| ظ | dḥā' | ðˁ | ḍh | () |

| ẓā' | zˁ | ẓ | () | |

| ع | !ayn | ʢ | ! | |

| غ | ghayn | ɣ | gh | |

| ف | fā' | f | f | |

| ق | qāf | q | q | |

| ك | kāf | k | k | |

| ل | lām | l | l | |

| in Allah | ɫ | ll | | |

| م | mīm | m | m | |

| ن | nūn | n | n | |

| ه | hā' | h | h | |

| و | wāw | w | w | |

| و | (as vowel) | uː | ū | |

| اَوْ | (diphthong) | oː | ō | |

| ي | yā' | j | y | |

| ي | (as vowel) | iː | ī | |

| اَيْ | (diphthong) | eː | ē | |

| other signs | ||||

| ء | hamza | ʔ | ' | |

| اَ | fatḥa | a | a | |

| اُ | ḍamma | u | u | |

| اِ | kasra | i | i | |

| اّ | shadda | (geminate) | ||

| اْ | sukūn | (no vowel) | ||

| آ | madda | 'ā | | |

| ٱ | waṣla | aː | ā | |

| اً | (nunation) | -n | -n | |

| ة | tā' marbūṭa | a(t) | () | |

| ى | 'alif maqsūra | a | | |

Notes

Arabic in Musa is written in Abjad gait, in which vowels are written above or below consonants, as in the traditional script. Normally, the letters are not connected. However, it is also common to see titles, company names and other labels in cursive gait and ornamental fonts. We'll talk more about that below.

Unlike in the traditional script, short vowels (َ fatḥa, ُ ḍamma and ِ kasra) are always written, and in fact vary their shapes to show the pronunciation.

Musa considers that the diphthongs ay and aw have become long vowels ey and ow. Unlike in the traditional script, the offglides of long vowels and diphthongs are also written above or below the consonants unless they form part of the root (in which case you can insert a Zero-Width Non-Joiner before the offglide to keep it as a consonant - the ZWNJ is available on Musa keyboards as Mapu). Long vowels (ah iy uw) are usually written with the Long mark, not the offglide.

The ّ shadda. isn't used: geminate (double) consonants are simply written doubled.

The ْ sukūn isn't needed.

There is no ٱ waṣla. If the initial hamza of the article is not pronounced, it simply isn't written. Since the Musa hamza doesn't need a "chair", there is no confusion.

There is no ى 'alif maqsūra. When a final ā is pronounced short, it's simply written as a.

There is no ة tā' marbūṭa . Normally, the feminine ending is just written as a fatḥa, but when it's followed by a vowel, Musa just adds a ت tā'.

Unlike in the traditional script, when the pronunciation of the definite article أَل 'al changes, either because it's followed by a "sun letter" or because it's preceded by a vowel, the written form follows the pronunciation.

The indefinite article is the suffix -n, but in traditional script, it is usually represented (if at all) by a doubling of the short vowel sign (e.g. هً) and the addition of a silent 'alif in the accusative case. In Musa, we just use the letter n for this nunation.

As shown in the table above, the pronunciation of the letter ج djim differs across the Arabic-speaking world. Everywhere, it should be written as it is pronounced, whether that is as dj, g or zh. The same is true for the many other variations in pronunciation: every dialect is written as it is pronounced, including the standard dialect.

If a short vowel is not pronounced at the end of the word (because of waqf), it's not written in Musa.

In Arabic, the stress falls on the penult (the second syllable from the end), unless the penult has only a short vowel and no final consonant, in which case the stress falls on the syllable before, the antepenult. Stressed vowels are written high, and unstressed vowels low.

Emphasis

Four consonants are called emphatic : ṣ ḍ ṭ and dḥ/ẓ. These sounds feature secondary pharyngealization : the root of your tongue is retracted as they are spoken. This retraction spreads to neighboring sounds in the same word, especially vowels. Five other consonants have a similar effect on neighboring sounds as emphatic consonants: q, r, ḥ, ', and a special "dark" pronunciation of the letter lam in the word Allah (and Musa uses a velar ɫ letter for this sound).

These changes are reflected in Musa. The following rules approximate an educated pronunciation of Modern Standard Arabic, although the actual rules are much more complex and not at all standard :

-

Coronal consonants s d t dh/z become ṣ ḍ ṭ dḥ/ẓ in the same word as an emphatic consonant.

Next to any emphatic consonant, the vowel a retracts to ah , and short i retracts to ih .

However, next to any other consonant except kh gh or ḷ, a advances to ae .

In any case, short a at the end of a word becomes ə .

Standard Spoken Arabic

As mentioned, the rules above only approximate an educated pronunciation of Modern Standard Arabic, because there is no standard pronunciation! Modern Standard Arabic is only a written dialect; every spoken dialect pronounces it differently. And one of the main reasons that there is no standard spoken Arabic is that the Arabic alphabet can't write many of the differences in pronunciation - they're all written alike. So perhaps the Arabic world is waiting for a more precise or less ambiguous orthography in order to develop a spoken standard. As in other widespread languages - Chinese, English, Spanish - a standard dialect wouldn't supplant the variety of spoken dialects: Arabic speakers would still be diglossic, as they are now. But the standard would include a spoken form.

Samples

Here is an example in some detail. We're going to write the name of the famous Caliph of Baghdad, Hārūn 'ar-Rashīd bin Muḥammad bin 'al-Manṣūr, the hero of the Arabian Nights. Here is his name in traditional script:

هَارُون الرَشِيد بِن مُحَمَّد بِن المَنصُور

And here's the same name in Musa :

Ornamental Styles

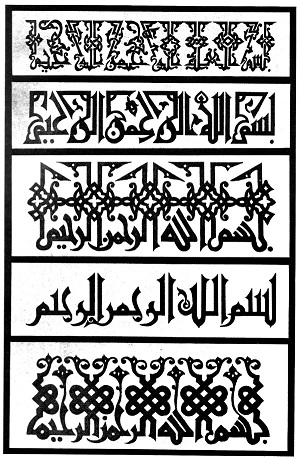

Because Sunni Islam proscribes figurative art, decoration in the Muslim world has focused on calligraphy and geometric patterns. Here are some examples in the traditional script, both old and new:

Because of this tradition, it is common to see Arabic names written in Musa in an ornamental style, especially when they are being used as labels, for instance on a book cover, a movie poster, a building or the like. Often, the font is either calligraphic (as if written by hand) or geometric, and it may also be cursive: the letters may be connected, like in the traditional script. For example, here is the same name you met above in a cursive gait : consonants are connected to form a zigzag spine, while the vowels are written in the spaces created above and below the cursive line.

The name Arabic on the Home page is also in a cursive font. Please bear in mind, as you compare the traditional and Musa versions, that traditional calligraphy has had fifteen centuries to develop their beautiful ornamental forms, while Musa is just beginning. If you are a calligrapher, perhaps you'd like to show us how beautiful Musa script can be.

For now, why don't you try reading a sentence?

| |

| البشر هم هم لايتغيّرون |

|---|

Islam

In addition to being the everyday language of 235 million people, Arabic is also the original language of Islam, the religion of almost a quarter of the world's population. Some Muslims may wonder whether the Qur'ān is just as holy when written in the Musa script.

The answer is "yes". As devout Muslims know, the prophet could neither read nor write, which is one reason why the Qur'ān is so beautiful : it was meant to be recited. So there is nothing holy about the traditional script itself. When Turkish converted from the Arabic script to the Roman alphabet in 1926 (as did Albanian in 1909 and Malay by 1959), this subject was widely debated, and an article appeared (by Kılıçzade Hakkı in Hür Fikir, 17nov1926) entitled "Gabriel didn't bring the Arabic letters too, you know". Most of the world's Muslims don't use the Arabic script, in fact, among the world's six most populous Muslim nations only one (Pakistan) uses it.

If the Musa script can write Classical Arabic better than the traditional script, then is it not a better vehicle for the Holy Qur'ān? And if the Muslims of the world write their own languages in the Musa script, won't it be easier for them to read the Qur'ān in the same script?

Here is the shahādah, the Muslim profession of faith which is one of the five pillars of Islam, written in the Musa script:

|

| |

| لا إلاه إلاالله و محمد رسولالله |

|---|

| © 2002-2025 The Musa Academy | musa@musa.bet | 19feb25 |