Chinese Characters

Chinese Characters

Chinese languages have been written in characters since at least 3000 years ago, although of course the script has evolved quite a bit since then. Alone among writing systems in use today (but like Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs), characters do not represent the sounds of the spoken languages, but instead represent meanings. Because of that, the same character can be used to write the same meaning in languages that pronounce it very differently. For example, the character 月 means "moon" or "month", even though it's pronounced yuè in Chinese, jyut in Cantonese, getsu in Sino-Japanese, tsuki in native Japanese, and wel in Korean. The funny thing is that most Chinese characters include phonetic elements, but the pronunciations have changed so much that the phonetics are at best hints, just like the English word knight is spelled in honor of its pronunciation in Old English.

To show how characters work, let's look at a typical example. Here is the character for cat, pronounced māo, in both traditional and simplified forms.

They're written with 15 and 11 strokes, respectively. The part on the left is called the radical, and represents a general meaning. In the traditional character, the radical

The two elements on the right of the characters for cat form another compound character:

The top element of miáo is another radical: it means grass. When it's on its own, it's pronounced cǎo (sounds like tsow) and written

Finally, the last element in the characters for cat is

So now you can see the logic: the word for cat, māo, is spelled with a radical meaning badger or dog, followed by a phonetic element pronounced somewhat alike whose meaning is irrelevant. It's like a rebus: try to think of a word that sounds like miáo but has something to do with small animals.

Lest you think I chose a complicated example, let's go back and look at the everyday characters for dog and grass. The phonetic element of gǒu

The phonetic element of cǎo

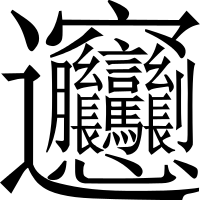

Characters get easier as you learn more of them: you meet the same elements again and again. There are 214 official radicals, and dozens more that aren't radicals, for a total of about 300 elements. They range from 1 to 17 strokes, although few have more than 7. And a typical character might have 2-4 elements, although some are much more complex. There's a type of noodle whose name is biáng: its character has 57 strokes!

But with some practice, these ~300 elements begin to function like an alphabet: they become familiar. They still only hint at pronunciation or meaning, the positions of the elements within a character are not pre-determined, and did I mention that the stroke order is important? You have to get that right, too. But with practice, patterns emerge.

If you grew up in China, you were told that characters are easier to read, easier to understand or have some other advantage. But compare the above with the English word cat, which is written in only five strokes and it tells you its pronunciation! And because it's written in an alphabet, it's much easier to sort into alphabetical order, to look up in a dictionary, or to type on a keyboard. And it is much, much, much easier to learn!

There's another hidden burden with characters that makes them even harder to learn: they have no relationship with the spoken language. When you learn a new word in English, you learn both the spelling and the pronunciation at the same time, because one represents the other. Even if you encounter a word with crazy spelling - like knight - for the first time in its spoken form, at worst you might think it was spelled night or even nite: you'd be wrong, but close. But in Chinese, you might learn the spoken word māo, and you'd have no idea how to write it - none! Likewise if you happen to encounter the written word 猫 first; you'd have no idea how to pronounce it. So spoken Chinese and written Chinese are two completely separate languages, and Chinese readers have to learn both of them!

And even though we say that characters represent meaning, if you encountered the character 猫 on your own, you would have absolutely no idea what it means. Even if you knew some Chinese, and you recognized the symbols that mean badger, dog, grass and field, you would probably not guess cat as the meaning. Of course that's true of any other language, too! The words cat chat gato Katze кот don't tell you anything about their meaning on their own - you have to know the language. But if you do already speak the language, you can hope to recognize the meaning on your own the first time you encounter the written word. Not in Chinese!

However, characters have two advantages that alphabets don't. The first is a degree of language independence. A Cantonese speaker from Guangzhou and a Chinese speaker from Beijing would not be able to have a conversation: those are two different languages, although China calls them "dialects". But although the pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar and word order are often different, they are both written in the same characters, so the northerner may be able to understand some written Cantonese. The situation is not so different from that between Spanish and Portuguese, for example: Spanish speakers can't understand spoken Portuguese, but they can usually read quite a bit.

This language independence also permits Chinese to read texts written in Classical Chinese, a language they would certainly not understand if read aloud. A very similar situation applies to the Arabic world, where native speakers each speak their own dialect, but only write a standard form. We used to have the same problem in Europe, where (church) Latin was the only written language, even though nobody spoke it as a native language. In these latter cases, this diglossia is rightly viewed as an impediment to literacy and development. Sure enough, when Europeans began writing their vernacular languages, Europe began to overtake the world! And nobody thinks that writing the English word knight as it was pronounced 1000 years ago is a Good Thing because it enables us to read Old English.

A second big advantage is disambiguation of homophones. Modern Chinese has only about 1300 syllables, including tone - far fewer than most languages (English has ten times as many). The result is an abundance of homonyms: syllables that sound alike. When they occur in a compound word, as is usually the case, the ambiguity is resolved. But when written, even a lone character presents no ambiguity. Because of that, until a century ago, written Chinese was very terse, in the style of fortune cookies. Since then, the Báihuà movement has encouraged people to write Chinese as is it spoken, so this is less of an advantage.

People who mention homophones as an impediment to sound-based orthography in Chinese need to remember that many languages have homophones - to too two in English; foi foie fois Foix in French - and that many languages have fewer syllables: Japanese has only about 100 syllables, and Hawai'ian has only 40! Obviously, if people can understand each other when speaking, then they can understand the written version of the same text!

The advantages of alphabets have been obvious to many Chinese, too. The May Fourth Movement of 1919, which began the New Culture Movement of the 1920s, proposed replacing characters with an alphabet, and this idea was supported by such giants of the era as Sun Yat-Sen, Mao Zedong, Qu Qiubai and Lu Xun. But when Chiang Kai-shek took over, the spirit of Western-inspired innovation was replaced by a return to nationalism and traditional values, and the script reform project was downgraded to a dual program of simplifying the characters and using an alphabet only in an auxiliary role. The result is the current situation, with pinyin in the latter role.

But stability has never been a hallmark of Chinese history, and the next change in direction, whenever it takes place, may see the pendulum swing in the opposite direction, and the idea of writing Chinese in an alphabet may again be raised. Hopefully, Musa will be considered for that role! Until then, Musa is an improvement over pinyin in the role of auxiliary spelling.

| Musa for Chinese > |

| © 2002-2024 The Musa Academy | musa@musa.bet | 02jul20 |