Dialects & Standards

Dialects & Standards

Two people that speak the same language don't, of course, talk exactly alike. People pronounce words a little differently, or even use different words. The language that you speak is called your idiolect. When you talk differently on different occasions or in different contexts, those differences are called registers.

But when many people share the same differences, that form of speech is called a dialect. Almost every language has different dialects - only languages with very few speakers don't. Sometimes the differences between dialects are great enough to make it impossible to communicate, even when both people agree they're speaking the same language.

When two dialects grow even further apart, we call them different languages. The point at which different dialects become different languages is determined politically, not linguistically. As Max Weinreich said, "A language is a dialect with an army and navy". For example, almost everybody agrees that Dutch and Afrikaans are different languages, even though they're mutually intelligible. And most people agree that Dutch and Flemish are different dialects of the same language, even though they're easily distinguished.

So far, we've only been talking about spoken language: language that uses sound as its medium. But written language is also language, and so is sign language. When we write 1 + 2 = 3, we're using a written language that has little to do with spoken language, even though it can also be spoken aloud. But most written language represents spoken language, even those (like Chinese) that don't represent sound. We could say that written language is a different dialect of a spoken language, or even a different language.

People usually write differently than they talk. If you read written English aloud to someone, they can usually recognize it easily, although when people speak self-consciously, they sound more like written English. Part of the problem is that written English lacks mechanisms for conveying the intonation that spoken English uses so much of. It's for that reason that Musa has accents to spell intonation. But even with Musa, we lack the gestures and facial expressions that complement the spoken words.

Other languages have similar differences, or even greater. French has a tense - the passé simple - that is only used in writing, never in speech! Chinese characters are the writing system for several different but related languages that can't be understood by each other's speakers. Written Arabic is unlike any spoken dialect but serves as the writing for all of them. Norwegian has two written forms of the same language, while Serbo-Croatian has two different scripts. The relationship between speech and writing is not simple.

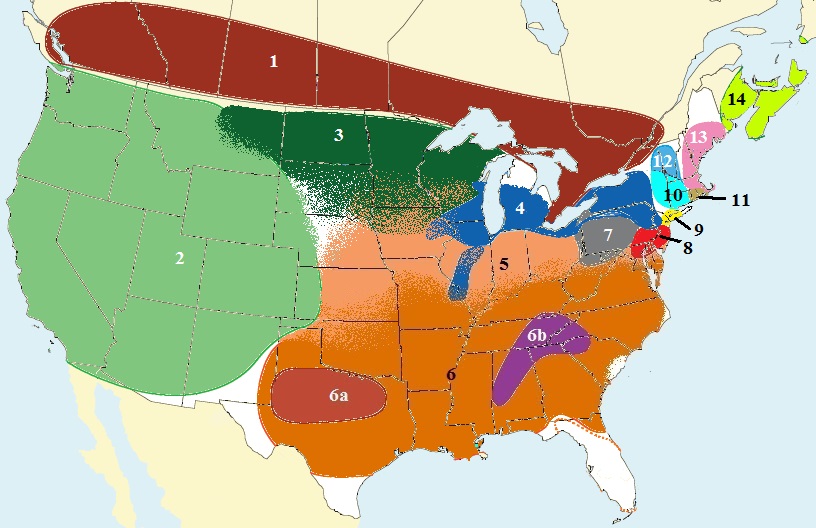

But let's talk about the differences between spoken dialects, using English as an example. The many English dialects can be divided first into (North) American English and Commonwealth English, which latter is then further subdivided into British, Australian, Irish, New Zealand, South African, Jamaican, and many more. The dialects of Great Britain can be further divided into Scots, Welsh, and the many different dialects in England. Here are two maps (from Wikipedia) showing rough dialect boundaries.

These dialects differ in vocabulary and grammar, but the primary distinction is in pronunciation, which we call accent. Commonwealth speakers say bɑth with a back a, while Americans say bæth with a front a. Yanks drink their cold beer with a rhotic r, while Brits drink their warm beeːə with a lengthening and perhaps centering offglide.

But they differ very little in spelling! Americans write color, center, defense and organize where Brits write colour, centre, defence and organise, but the differences are minor and easily overlooked. How can that be, when they pronounce bæth and bɑth so differently, and say truck vs. lorry? The answer is that all English speakers write to a standard: there is a standard form of written English that differs little across the globe, at least in spelling.

Ironically, that's made much easier by the fact that English spelling doesn't track pronunciation very well, so everyone just recognizes a word without sounding it out. But that means that words are not spelled as they're pronounced, and so everybody has to learn the spelling in addition to the pronunciation and the meaning. That extra work is what's costing us those three extra years of education: learning that too is spelled to when it's a preposition and two when it's a number, in addition to its "normal" spelling of too as an adverb. This work is made harder when the spelling is very odd: won and one sound alike, but only one - won - is written close to its sound.

So is Musa written to a standard, or - since it's phonetic, or at least allophonic - does everybody write like they speak? Well, something in between. Musa is usually written to a standard, but in an ideal world, every dialect would have its own standard. Scots English, Ozark English, and Australian English would look as different in writing as they sound, and people would understand them the same way - with a little bit of difficulty, but not enough to impede communication, just as we now do with vocabulary: Brits take the lift to their flat, while Americans take the elevator to their apartment, and it isn't a problem.

In this world, lexicographers publish dictionaries with the correct spellings of words, and nowadays, those dictionaries are incorporated into spell-checkers and transcribers, just as we have now. And like now, you choose a dictionary for your dialect.

The difference with Musa is that there will be many more different dialects. Fortunately, we now have the technology to deal with that. Most dictionaries will cover several, if not many, dialects, and ask you to choose the one you want. For example, if your dialect has the "weak-vowel merger", so that Rosa's and roses sound alike, then the dictionary will use a Musa schwa for most reduced vowels. If not, it will show you which use schwi, and which use open schwa.

The big advantage is that people can learn to write like they speak. If the written language hews closely to the spoken, we can rely on that to resolve dialectal differences, disambiguate homophones, and follow language change. If we decide to establish a "neutral" written standard, we lose all that. Arabic and Chinese (until a century ago) are examples of the diglossia that arises from such standards. And in practice, it's often easier to understand a difficult dialect or language when written, just because the hard work of parsing has been done for us.

If speakers of African-American Vernacular English say wif and aks, why should they have to learn to write with and ask, as if it were a foreign language? But just as most AAVE speakers can switch to General American, they will learn to write General American as well. That's what happens now with, for example, Moroccans who speak and write Dariya for a local audience, but speak and write Modern Standard Arabic in a more formal setting. And in fact we all do that already: we have all mastered various registers and when to use each one. A richness, not a problem.

| © 2002-2025 The Musa Academy | musa@musa.bet | 28dec24 |