A Tighter Phonetic Alphabet

A Tighter Phonetic Alphabet

As the IPA celebrates its 125th birthday, it's showing its age. We don't still rely on many other 19th century technologies - the typewriter and the telegraph are just memories. It's time for us to revisit our phonetic notation. Despite all the new media, we're still going to be using it for a long time.

On this page, I'll talk about how the IPA is failing us. Then on the next page, I'll introduce an alternative called the Musa Alphabet that solves the IPA's two main flaws - its decision to describe most consonants as modified versions of other consonants, and its articulatory model for vowels - as well as offering the benefit of being completely featural. The IPA also has a number of smaller flaws; Musa solves some of them and shares some others. No transcription system is going to be perfect, but we can - and should! - demand more than the IPA offers.

Here are some example of the IPA in use ... or not:

In dictionaries

Here are screenshots from six online dictionaries. The two American dictionaries at left don't use IPA at all. The two online-only dictionaries in the center column offer it as a secondary option. And the two British dictionaries on the right use IPA, but only a phonemic transcription: they're using IPA symbols, but not with their IPA sound values! That's not very helpful, especially for non-natives who don't know English phonology.

In education

Here's a "periodic table" of English sounds for Spanish-speaking learners from the popular Babbel program. See all the IPA? I don't either.

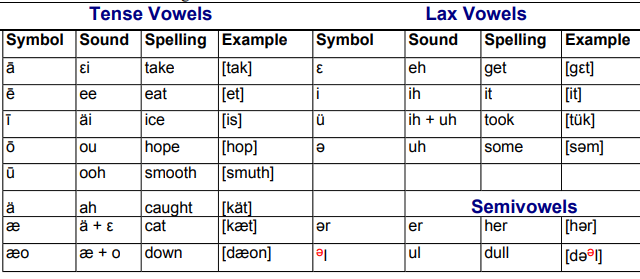

Here's a table of English vowels from a course for people who want to improve their American accent:

You might think these charts didn't use IPA because they were also trying to teach English orthography ... until you notice respellings like klaak and tük. No, they're actually inventing new phonetic spellings for English just for use in this series of lessons! One more complication for their students on their way to learning spoken English, and one that will have no other use later.

In the press and tourist guides

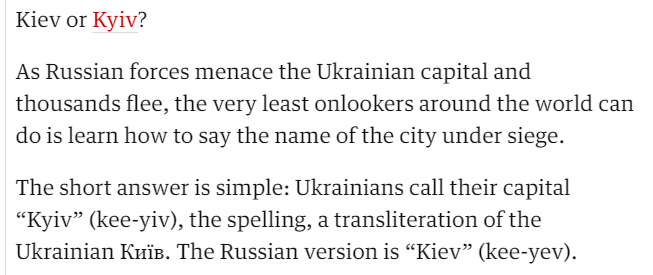

Here's the beginning of an article from The Guardian on how to pronounce Ukraine's capital city:

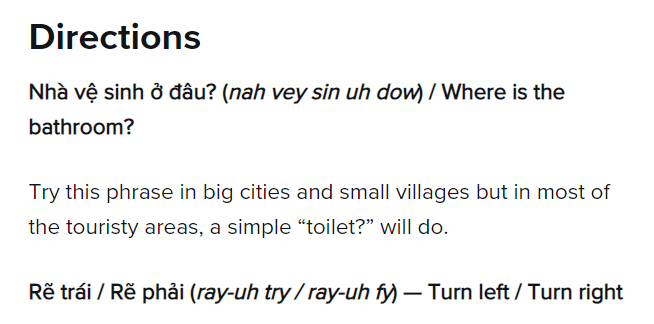

Here's a similar approach in a tourist guide, to help you pronounce some useful phrases:

And Spanish is one of the easiest languages for English speakers to read in its traditional orthography: quite phonemic, and a familiar alphabet (except for ñ). Here's Vietnamese:

In academic linguistics

The IPA isn't even used by all linguists. Scholars working with indigenous languages of the Americas, Caucasus, and India; Slavic, and Semitic languages often use a different alphabet, the APA Americanist Phonetic Alphabet (there was also a SPA Slavistic Phonetic Alphabet). Linguists working on Uralic languages often use the UPA Uralic Phonetic Alphabet, while those working on Afro-Asiatic languages use Afrasianist Phonetic Notation. Despite Unicode, we still run across X-SAMPA and Kirshenbaum transcriptions, for example as input to Praat. The existence of all these different phonetic alphabets is testimony to the shortcomings of the IPA.

All of these cases should be using a standard international phonetic alphabet that kids are taught in primary school, like they learn the metric system or international traffic signs. But the IPA is not suitable for such wide use. In the words of Geoff Lindsey, "Most people that I encounter find even the familiar IPA phoneme symbols for AmE or BrE to be frighteningly unfamiliar and technical!". If we had a phonetic notation that was clear and useful, everybody would learn it and use it. That's not too much to aim for.

Even when the IPA is used, it's often used sloppily.

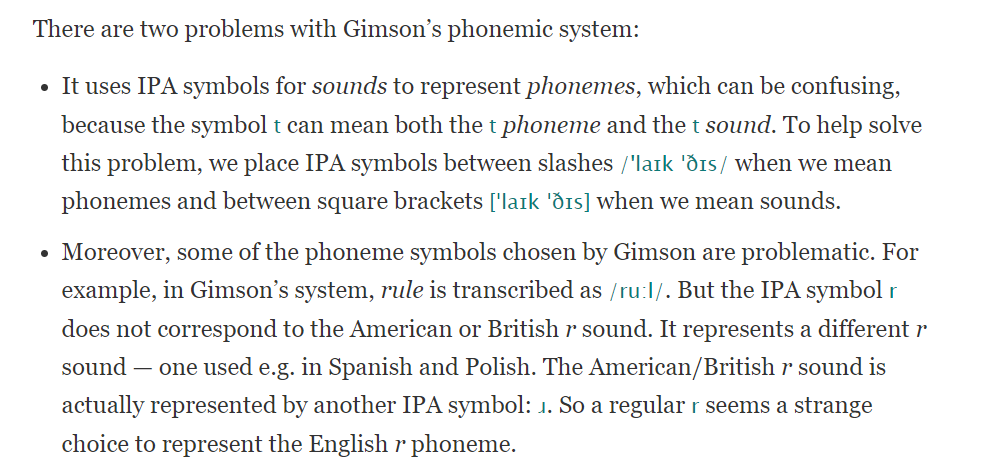

Phonemic transcription

The transcriptions in the dictionary entries above are phonemic, as shown by the slashes. That means it uses the IPA symbols, but not with their IPA sound values. It's as if these dictionaries want to be able to say that they use the IPA, but they don't actually want to use it.

And of course, a phonemic transcription is pretty useless for people who don't know English phonology, like foreigners. To understand it from their perspective, consider a foreign example: a phonemic transcription of the name of Japan's most famous mountain is /huzi/ (hoozy?). Only if you know Japanese phonology would you be able to convert that to [ɸɯʑi] or even Fuji.

Their phonemic transcription of tight is /taɪt/. A narrower, allophonic, transcription of tight would be [ˈtʰäɪ̯̆t˺]. We can excuse the centralized a and pre-fortis clipping as being too detailed for this level of transcription, but the same can't be said for the aspirated initial t, the non-syllabic offglide, and the unreleased final. Without those diacritics, the word [taɪt] might be tied, died or diet ! (In English, next to pauses, lenis d is devoiced d̥, which sounds like tenuis t.)

The IPA doesn't specify which allophone to use to represent a phoneme. But if the IPA had a single letter for an aspirated tʰ, one that didn't need a diacritic, I bet that's the letter the lexicographers would have chosen for the initial phoneme in /taɪt/. And for native speakers of the many languages with both tenuis and aspirated plosives - the Indo-Aryan and Chinese languages, Thai, and Armenian, among others - omitting the aspiration just makes it wrong. Likewise for the unreleased final.

Here's another example, the word north from the sample phonemic transcription of American English in the Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: /ˈnoɹθ/. The corresponding phonetic transcription is [ˈnɔɹθ], even in dialects with the cot-caught merger (as illustrated here), and in fact NORTH is the keyword John Wells chose for that lexical set. So substituting the close-mid o for the open-mid ɔ is not abridging detail; it's just using the wrong letter!

The explanation can be found in section 5 of the Introduction to the IPA at the beginning of the Handbook. There, we read that a broad transcription "sometimes carries the extra implication that, as far as possible, unmodified letters of the roman alphabet have been used." In other words, broad transcriptions can use just the Roman alphabet, even if it doesn't spell the correct sound: the real IPA is just too difficult!

Phonetic transcription

This sloppiness extends down to narrow phonetic transcription. Here's an example, the narrow transcription of American English from the Handbook. I've added (in red) some missing symbols.

The adjacent section on Conventions explains that "[p, t, k] are aspirated in word-initial position, and elsewhere when initial in a stressed syllable...", but aspiration isn't shown in the transcription, even though it's described as "a narrow phonetic transcription in which the conventions and other details have been incorporated."! This transcription also omits the offglides, the non-syllabic diacritics in words like əˈɹaʊ̯nd and ˈʃaɪ̯nd, the unreleased final fortis stops, the devoicing of lenis plosives next to a voiceless sound or a pause, the underscore for retraction in t̠ʃ and t̠ɹ, the assimilation of n to ɱ in kəɱˈfɛs, and the velarization of ɫ in ˈfoɫd. The IPA can write all this - that's what the IPA is for! - but even phoneticians don't bother, not even in a passage intended to demonstrate the power of the IPA!

In all these cases, the abridgement isn't being done for phonetic reasons; it's being done for typographical reasons. If the IPA didn't need all these dīacrĭtics, digraphs, tuɹns, ɦooks, ɕurȴs, and tailʂ - if each sound just had its own letter - then we wouldn't be leaving them off.

The case of the Indian plosives

Does this matter? Isn't this all just nit-picking? Consider the fact that one of the hallmarks of the English spoken in India is that fortis stops p t ch k are unaspirated (tenuis). There are many languages in the world which don't use aspiration, and native speakers of those languages have trouble with aspirated pʰ tʰ chʰ kʰ. But that's not the case with the Indo-Aryan languages like Hindi and Bengali - they do distinguish aspirated and unaspirated plosives. So why do their native speakers have trouble with those sounds in English, if they're present in their native languages?

Maybe it has something to do with the transcriptions. Maybe they first encountered the Roman letter t as the IAST romanization of त or ত, unaspirated letters. Or maybe their textbooks use /t/ and not /tʰ/ as the symbol for the fortis t phoneme. Is it possible that careless transcription has lead the world's largest community of English speakers astray?

As you all know, the Romans used Roman numerals like XIV. In other words, the Romans - like the Greeks and the Hebrews before them - used to write numbers using letters! And why shouldn't they? Those letters were already familiar; why invent new notation? But in fact, Roman numerals aren't a great notation, and mathematics only took off after the current notation was introduced (in the 12th century when Al-Khwarizmi's book presenting the Hindu numeric notation was translated into Latin).

We're in a similar situation now with phonetic notation. One of the original principles of the IPA was to use Roman letters as much as possible - and why shouldn't they? The founders all used the Roman alphabet for their native languages, and they wanted to avoid having to cast new type - that's why so many of the IPA letters are upside-down Roman letters. From there, it was natural to add decorations (hooks, tails, curls, strokes, ...), diacritics, digraphs, script, Greek, and small-cap forms.

The result is that the vast majority of IPA letters are modified variants of other letters, not letters in their own right. Letters like ɓ β ʙ are read as "some weird kind of b"; only the hook of the implosive carries a hint of what kind of weird b they are. Letters like ɔ ɟ ʌ ɯ ɥ ʎ are even worse: they don't have any phonetic relationship at all with the base letters. And the various decorations aren't used consistently: ʙ isn't uvular, ɦ isn't implosive, and ɮ isn't an affricate.

Even unmodified letters are sometimes misleading. The fact that the IPA is based on the Roman alphabet should be an advantage for those of us who use that alphabet for our own languages, but this advantage is reduced or even reversed if the letters don't stand for the sounds we expect. For example, IPA j q x y and many vowels don't stand for the same sounds as they do in English … but at least there are other languages that spell those sounds that way.

But now look at the letter c. It stands for a k or s sound in English, French, Catalan, Portuguese, and Italian. In German, Polish, Hungarian, Croatian, Albanian, and even Chinese pinyin, it stands for ts. It has a few other values: th sh ch dj, even a click or a glottal stop. But in the IPA, it stands for the voiceless palatal plosive, the sound written ty in Hungarian and t' in Czech. Who writes that with a c, the Dinka? So much for IPA principle #4: "In assigning values to the Roman letters, international usage should decide.".

In one of John Wells' books, he tells the anecdote of slipping the trap word [reply] into an IPA reading-aloud exercise for his graduate students: in IPA, the letter y stands for a close front rounded vowel, but almost all of them read through it as English reply.

A particularly noteworthy case where the current IPA vowel chart seems deficient is in the notation for an open central vowel, perhaps the most frequent vowel in the world, for which there is no IPA symbol. Barry and Trouvain reopened the debate in 2008 after discussion at the 1989 Kiel conference ended with no action, and Sally Thomason discussed it the same year in her article "Why I don't love the IPA", but in the 15 years since, the issue remains unresolved. Coincidentally, the most common vowel in English - the near-back near-close schwi - is also not represented by an IPA vowel letter.

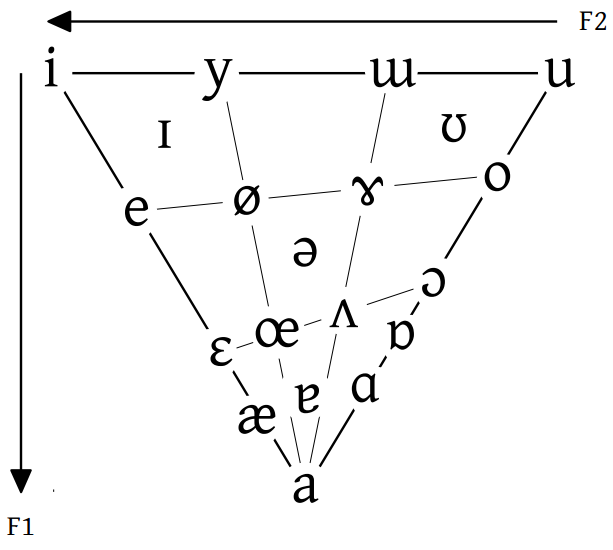

The founders of the IPA based their vowel chart (top left, below) on articulatory dimensions, an approach which we now know to be inaccurate. The other images show most of the same vowels from an acoustic perspective, arrayed by (log) formant. You can see that nine central vowel symbols ɨ ʉ ʏ ᵻ ɘ ɵ ɜ ɞ ɶ are missing, and ɒ has just been squeezed in. Those missing vowels could be placed on the triangle, but they wouldn't add any value - they'd be too close to their neighbors to be useful.

You can see that in the three acoustic images (click to see the sources), most central vowels don't appear - they're just not useful. This is a clear case of the IPA simply showing its age: we didn't have the technology back in 1887 to plot formants on an acoustic chart. But now we do.

Look at the Retroflex column on the IPA chart: ɳ ʈ ɖ ᶑ ʂ ʐ ɭ ɽ ɻ. Each of the symbols is simply the symbol from the coronal column to the left, augmented with a right-swinging tail. They even add the tail to IPA symbols like ᶑ and ɻ that aren't basic Roman letters. As a result, nobody has to think twice about the symbols for retroflex sounds - easy!

Now look at the Palatal column to its right: ɲ c ɟ ʄ ç ɕ ʑ ʝ ʎ j. Three of them have little curls, but there's no rhyme or reason to the group. To learn them, you just have to memorize them! And unfortunately, most of the IPA is arbitrary like the palatals, not featural like the retroflex. It's just a jumble of random symbols.

Contrast that with Musa, where every column shares a bottom, and every row shares a top. If you know the Musa letter for a velar, like k, then you know you can deepen the bottom to write the uvular: (the IPA is q - how could you know that?). That makes Musa much easier to learn.

I once met an elderly gentleman who did the crossword puzzle every day without looking at the clues. How did he do it? Easy: he just didn’t care whether the rows and columns formed words. As long as every box in the grid was full, he was happy. That’s how I see defenders of the IPA: as long as every box in the grid is full, they’re happy; they don’t care if the rows and columns make sense.

That sure does make the IPA much harder to learn and remember.

The IPA solves a real problem, and we're all better off for that. Unfortunately, it doesn't solve it very well, and that's a shame. The creators of the IPA were competent and smart, and they worked hard with the best intentions, but it's like the old joke that a camel is a horse designed by a committee: the IPA isn't faithful to its own guiding design principles, it tries to please all constituencies, it gives too much respect to legacy solutions, and it ended up as a patchwork of ad hoc fixes.

| Musa as a Phonetic Alphabet > |

| © 2002-2025 The Musa Academy | musa@musa.bet | 06aug24 |