Musa as a Phonetic Alphabet

Musa as a Phonetic Alphabet

On the last page, I explained how the IPA isn't as good as it should be. On this page, I'll present an alternative, the Musa Alphabet. Musa isn't perfect - no transcription scheme is - but it demonstrates what we could have. Unlike the IPA, Musa was not adapted from a legacy orthography; it was designed from the ground up to be a phonetic alphabet. As you'll see, that's a big advantage.

Musa At A Glance

The Musa Alphabet is a featural phonetic alphabet designed to write all the world's languages. It's encoded in the Private Use Area of Unicode, at E000-E2FF. Musa letters are each composed of two shapes, drawn from a set of 26, shown here on a standard keyboard (the two black keys are Backspace and Enter):

In each letter, one shape is on top; the other on the bottom. If either is a space (the key with a · dot) or an accent (the 3 lines in the next column), the letter is a vowel. If both are, it's punctuation. Accents spell tones and, as punctuation, intonation. High vowels spell stressed syllables. Here's I see it! written in Musa:

The shape of each vowel indicates its sound. Rounded letters spell rounded vowels, and unrounded letters spell unrounded vowels. Closed letters spell closed vowels; open letters spell open vowels. Lazy (sideways) letters spell lax vowels. Triangular letters spell front vowels, and square letters spell back vowels. There are no separate letters for central vowels.

Tall letters are consonants. If the top is a vertical line, it spells a semivowel (like English y, above) or suffix (the same letter spells Russian ь or IPA ʲ). The other tops indicate manner of articulation:

The triangular shapes have been skewed to one side to connect better.

The triangular shapes have been skewed to one side to connect better.

The bottom of a letter indicates place of articulation:

The hissing, hushing, rustling, and humming bottoms are sibilants or affricates.

Here's a more colorful version of that same information:

In Musa, each sound is spelled with a single letter.

And that's pretty much all you need to know to use Musa - not so hard :)

The next page describes the prefixes and suffixes that Musa can use to describe pronunciation in even greater detail, which we call orthophonic transcription. The page after that introduces a number of other useful tools for Musa phonetic transcription. But before proceeding, let's step back and look at the bigger picture.

Comparison with the IPA

The current version of the IPA consists of 28 vowels and 79 consonants, for a total of 107 letters. It also includes 32 diacritics, 9 suprasegmental marks, and 24 tone marks in two systems. That's a total of 172 signs, 173 counting the space between words.

Musa, on the other hand, includes only 22 vowel letters, 6 accents for tone, and 24 punctuation symbols, including the space. However, it offers many more consonants - 192 so far - plus 55 more orthophonic suffixes (that play the role played by diacritics in the IPA). That's a total of almost 300 signs, twice as many as the IPA.

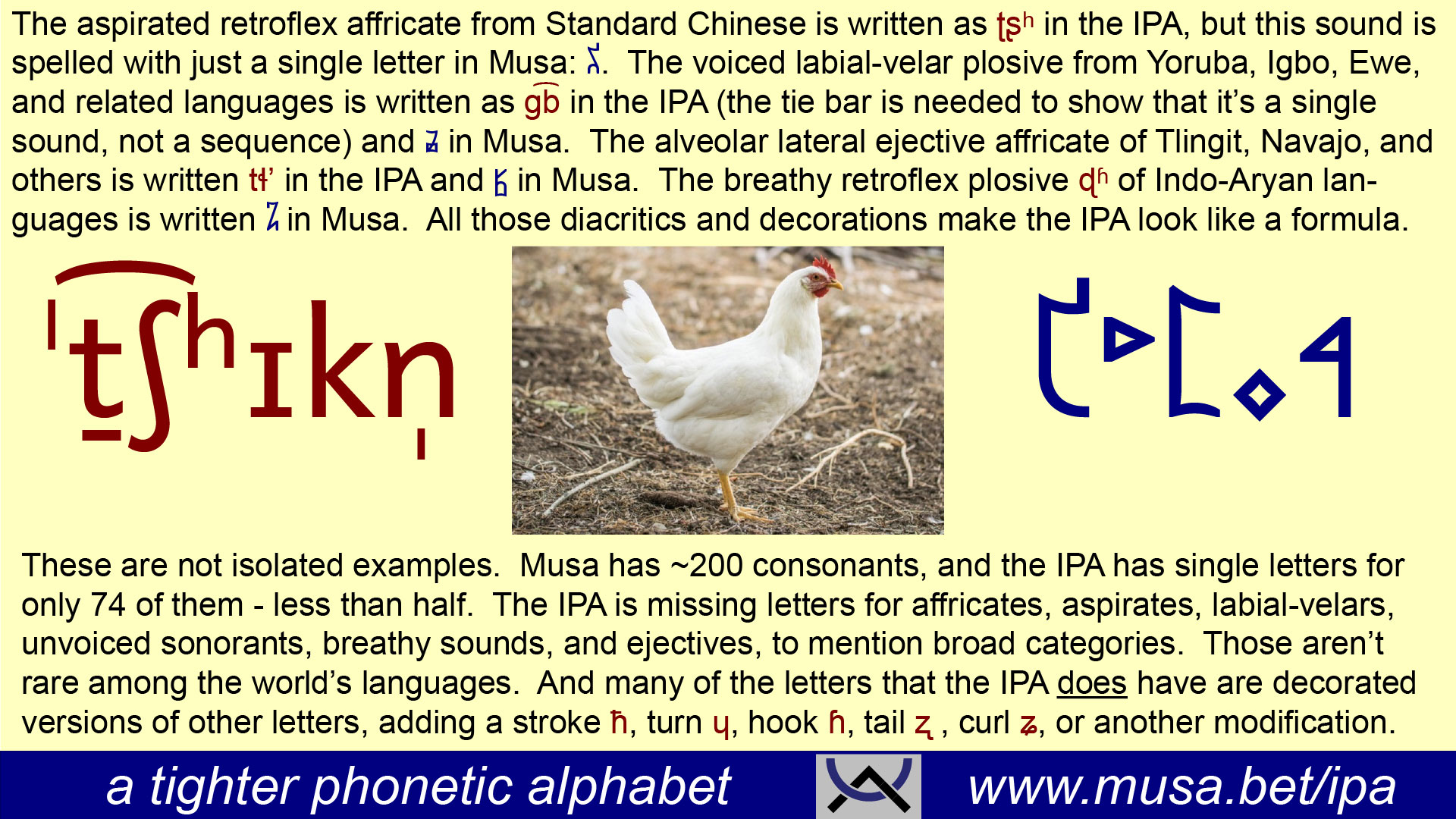

The IPA relies heavily on modifiers: diacritics, digraphs, ligatures, decorations like strokes, hooks, curls, and tails, turned letters, cursive letterforms, Greek letters, and small caps. That made sense back in the 19th century, when IPA symbols had to be created by repurposing or modifying existing metal type. But now, in the digital era, those modifications read like afterthoughts, as if the sounds they represent were somehow less important. That's why they're so often omitted in broad transcription.

Some of the IPA letters are featural. For example, the letters for retroflex sounds all feature a right-swinging tail: ʈ ɖ ɳ ɽ ʂ ʐ ɻ ɭ. The central nasals are all variants of n: ɳ ȵ ɲ ŋ. The implosives all sport hooks on top: ɓ ɗ ʄ ɠ ʛ. Many small caps spell uvular sounds: ɴ ɢ ʀ (and ʟ ʜ are close, but ʙ is not).

But other IPA letters are harder to justify. Several IPA letters are simply "turned" versions of other letters, since it was easy to repurpose the slugs of 19th century typesetting by simply turning them over. In some cases, the turned letters denote related sounds, like ɹ ʍ ə ɒ ʎ. But in others, like ɯ ʌ ɔ ɟ ɥ, the turned versions have nothing to do with the originals, phonetically. Nor do the decorations convey a consistent meaning. One lateral fricative ɬ added a belt; the other ɮ is a ligature. Strokes are shared by palatal plosives ɟ and implosives ʄ, a pharyngeal fricative ħ, and a velarized alveolar lateral ɫ (in addition to t and f). Palatal fricatives add curls to a plosive ɕ, a sibilant ʑ, and an approximant ʝ, but the fourth uses a cedilla ç. There's no rhyme or reason.

In contrast, Musa is completely featural: all the consonants articulated in the same position share the same bottom, and all the consonants articulated in the same manner share the same top.

Examples

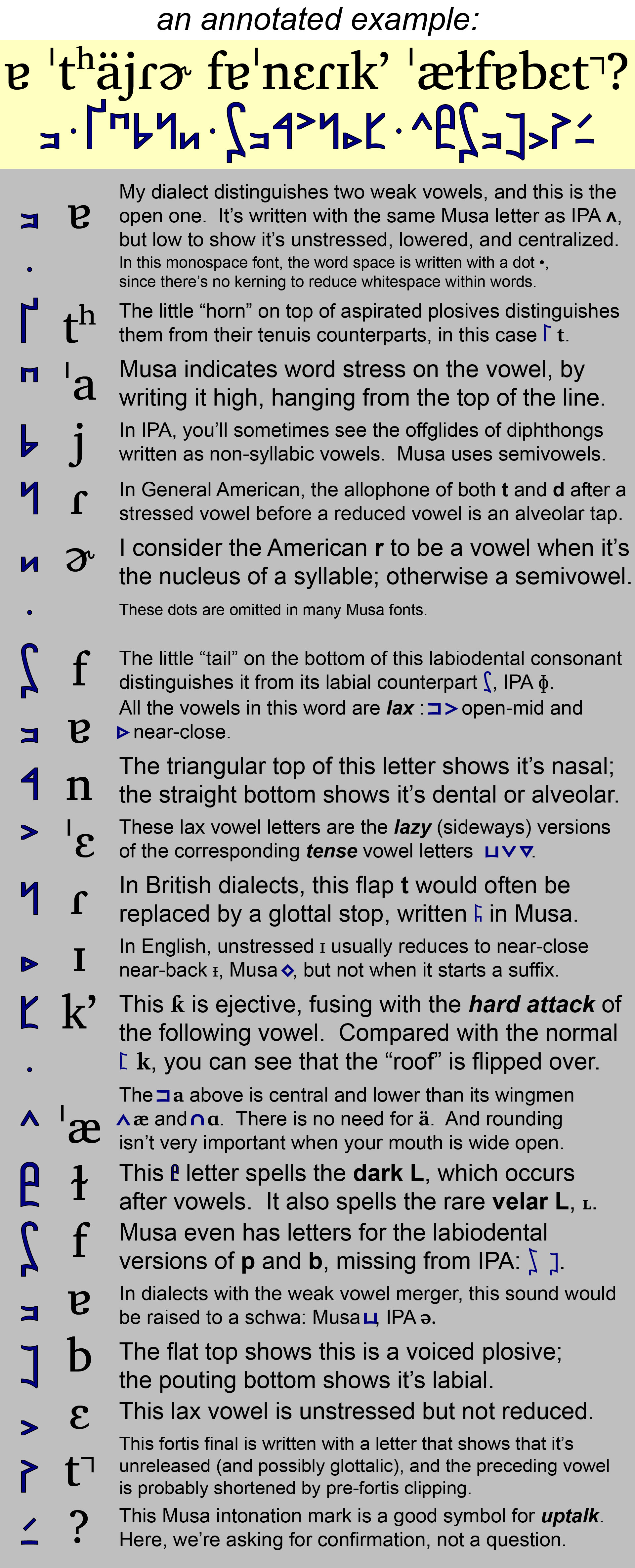

Here's a narrow transcription of the phrase "A Tighter Phonetic Alphabet" in both Musa and IPA, so you can see how they line up:

And here's a table showing the word chocolate in several languages, in both IPA and Musa. The two versions carry all the same information - the Musa is much cleaner.

| lang | orthography | IPA | Musa |

|---|---|---|---|

| en | chocolate | ˈt̠͡ʃʰɔːklᵻt̚ | |

| zh | 巧克力 | t͡ɕʰi̯ɑʊ̯˨˩˦kʰɤ˥˩li˥˩ | |

| hi | चॉकलेट | ˈt̠͡ʃɔːkleːʈ | |

| es | chocolate | t̠͡ʃokoˈlate | |

| fr | chocolat | ʃɔkɔla | |

| ar | شُوكُولَاتَة | ʃuːkuːˈlaːtah | |

| ru | шоколад | ʂəkʌˈɫat | |

| ja | チョコレート | ɕokoreːto | |

When using Musa as a phonetic alphabet, we usually render it in the Dushan Musa Alphabet font, a monospace font that doesn't use any Advanced Typography, even though several of these languages are normally written in other gaits. Hover the cursor over the Musa above to see the other gaits.

Musa offers a number of smaller advantages over the IPA:

-

The Musa letters are easily handwritten, while many of the IPA letters are not. In fact, the IPA letters are not even available in many fonts - that's why X-SAMPA was invented. Of course, Musa letters are only available in Musa fonts.

An IPA keyboard requires separate keys or key combinations for all 173 signs. As far as I know, a physical IPA keyboard has never been produced. A Musa keyboard writes all the Musa letters with just 26 keys: just use your normal keyboard in overlay mode or a screen keyboard on your computer or phone. You can even use your phone as a Musa keyboard for your computer.

The IPA symbols have names like ʎ "turned y" and œ "lower-case O-E ligature". The Musa letters have much simpler names: only two syllables for consonants and one syllable for vowels. For example, the names of the Musa letters for ʎ and œ are pupi and wa.

The IPA has diacritics to mark stress, tone, and intonation, but they don't match other orthographies. For example, the name (in standard Chinese) of chess grandmaster 丁立人 is spelled Dīng Lìrén in pinyin, but tíŋ lîɻə̌n in IPA. Here are those two romanizations again, large enough for you to see the tone marks clearly:

In contrast, Musa writes stress with vowel height, tone with simple accents, and intonation with punctuation. The Musa notation for stress and tone is so natural that it's not omitted (a big problem in African languages, for instance). Think how often you see IPA without stress and break marks.

OK, so Musa may be a worthy successor to the IPA - so what? Most things designed in the 21st century are better than their 19th century equivalents. But the IPA is so well-established - do we really need to learn something new?

I've asked the same thing myself many times! I asked it when books and journals started appearing on screens: I prefer reading from paper. I asked it when mobile phones first came out: why do I need to be in touch all the time? Then I asked it again when smartphones first came out: do I really need to surf the internet while I'm on the bus?

But in the end, the advantages of Musa make it worth the transition: it's easier to learn, easier to read, and easier to write. Yes, it will take a modest effort to learn, but less than you probably imagine. And nowadays, everyone on the bus is using their smartphone.

So let's get on the bus :)

| < A Tighter Phonetic Alphabet | Orthophonic Transcription > |

| © 2002-2025 The Musa Academy | musa@musa.bet | 29apr24 |