More Voices

More Voices

The letters you met on the last page enable us to write sounds with manners and positions of articulation beyond what we can do with the basic letters, but we can also write sounds with different voices. I mentioned voice above to distinguish between pairs of letters like p-b, t-d, k-g, f- v, and s-z in English, but that's only part of the story. Here's the unabridged version.

The difference between t and d in English is that the vocal cords vibrate as you say voiced d, while for aspirated t they don't start vibrating until a few milliseconds after the plosive release. English actually has a third sound in this family : the unvoiced and unaspirated t in words like stop : if you put your hand over your mouth, you can feel a puff of air after tear that you don't feel after steer or deer. Linguists call that middle sound tenuis, since the voice onset and the plosive release occur together. This tenuis t is the sound of French t and Chinese d.

It's even more complicated than that. In English, when a voiced sound occurs after a pause or an voiceless sound, the voicing doesn't start right away (when the articulators close). Instead, it starts midway through the closure. Linguists call that partial voicing, specifically final voicing. Likewise, when a voiced sound occurs before a pause or an voiceless sound, the voicing may end before the release, and we also call that partial voicing, specifically initial voicing. In Musa, we group all three of these middle sounds together - tenuis, final voiced, and initial voiced - and we'll call them all unvoiced. Thus we use unvoiced letters if the voicing is interrupted, no matter whether it's for the whole articulation or just part of it.

But timing isn't the end of it. When we pronounce voiced d, our vocal cords are vibrating modally, at their optimum frequency. But in some languages, there are sounds with the vocal cords looser or tighter. Looser phonation is called breathy voice or murmur, and tighter phonation is called creaky voice. There are even half-loose and half-tight phonations called slack voice and stiff voice, respectively : they contrast with each other in Javanese. There are also different phonations produced by modifying the vocal tract above the glottis, for instance harsh and hollow voice. I'll call all six of these laryngeal voices.

Those categories cover (almost) all the voicings used contrastively in languages, but there are several more ways to make interesting sounds using your larynx. When we whisper, we make a voiceless sound without opening the glottis. Falsetto is a very high voice. There are also vocalizations with the larynx raised or lowered, and others called ventricular and pressed (or tight voice) and strident. Finally, there are sounds made by people with unusual vocal tracts, perhaps because of a cleft palate or other defect, because of injury or surgery, or because of neurological problems. Since they generally aren't used in normal language, we'll postpone any discussion of these for a future page on Voice Quality.

All these sounds work by modifying the airstream we squeeze out of our lungs as we talk. But there are also three types of sounds made by using a different airstream mechanism. Some languages feature ejective sounds, which are made by closing the glottis and raising the air pressure in the mouth so as to produce a very strong release. The opposite are implosive sounds, which are made by lowering the pressure in the mouth before release. The third type is clicks, which involve two closures in your mouth - we'll discuss them later.

Let me array the voicings used in languages on a spectrum from least breathy (stiffest) to most breathy (slackest):

- closed glottis (glottal stop)

- implosive (with closed glottis)

- held = unreleased (with closed or open glottis)

- harsh

- creaky (laryngealized)

- stiff

- (modal) voiced

- slack

- breathy or murmured

- hollow (faucalized)

- unvoiced

- aspirated

- ejective (with closed glottis)

We'll talk about the blue ones on this page, and the black ones on the next page.

Many languages need only voiced and unvoiced :

By the way, I'll try to be consistent in my terminology. I'll use unvoiced to mean tenuis or partially voiced. I'll use voiceless to refer to all of the phonations without voice, thus including aspirated, held, ejective, and even murmured sounds (which have some voice). I'll also use voiceless when talking about sonorants. But voiced will only mean fully modally voiced. And I'll use devoiced to refer to phones that occur when a voiced phoneme becomes unvoiced.

Aspirated Consonants

Standard Chinese contrasts two phonations, but they're not voiced versus unvoiced. Instead, the contrast is between aspirated and unaspirated. The Thai language contrasts three phonations : stiff consonants for which we use the basic voiced letters, unvoiced sounds for which we use the basic unvoiced letters, and aspirated sounds for which we use these aspirated letters. Ancient Greek also had voiced β δ γ, unvoiced π τ κ, and aspirated φ θ χ (as well as affricated ψ ζ ξ), although two of those series now represent fricatives in Modern Greek.

The letters for aspirated sounds look like the unvoiced letters you already know, but the rooftop has a short chimney sticking up from the end:

Above, I described aspirated sounds in terms of the voice onset time, but a far more salient indication is the little puff of air emitted with the release - you can even feel it with your hand in front of your mouth. That's why these consonants are often spelled as a digraph with h or superscript ʰ, as in pʰ tʰ kʰ. Even the Greek letters φ Phi, θ Theta, and χ Chi originally spelled aspirated sounds (before becoming lenited to fricatives).

Musa doesn't need to write more detail, but you should know that the actual situation is, as usual, more complicated. The aspirated stops of two different languages might be quite different. For example, those in Chinese have much longer voice onset lags than those in English. The aspirated stops are also often marked with other acoustic cues that may be just as important as voice onset time. But as far as I know, no language contrasts two different levels of aspiration with long lags.

Some languages have pre-aspirated stops, where the aspiration comes before the stop. In Musa, we write them with a preceding h, as if they were normal consonant clusters, as several languages do.

Breathy Obstruents

Most of the Indo-Aryan languages have a fourth phonation : a breathy voice which they consider to be the voiced version of an aspirated consonant (or the aspirated version of a voiced consonant). Alternatively, some languages have voiced consonants with a breathy release. To represent these sounds, Musa uses basic voiced letters with a short vertical line, but in this case it's hanging down, a downspout from a flat roof:

Voiceless Sonorants

Sonorants include nasals, laterals, taps, trills, and approximants. They're normally voiced, but they can be unvoiced or breathy: breathy sonorants are said to be murmured, since the breathiness is held for the whole sound, not just the release. Musa uses the same letters for unvoiced and murmured sonorants; we'll call them voiceless.

Voiceless nasals are written with the triangle on the other side, and symmetric.

Voiceless laterals are written with the arch upside-down, with the flat part on top:

Voiceless taps and trills are written with the zigzag closed at the top:

Voiceless approximants are written with a half-oval on the other side:

Some scholars consider it impossible to have voiceless approximants - they say they're actually fricatives. And yet they're common in Sino-Tibetan languages. I read somewhere that frication starts about halfway through. At any rate, even if they're really half-fricatives, Musa has letters for them.

The voiceless w - IPA ʍ - is the sound in English words like where or whale in those dialects that pronounce them differently from wear and wail. This sound is also sometimes pronounced as hw, a pre-aspirated w. With it, we'd write whine as .

Fortis and Lenis

In English, German, and some other languages, the situation is more complex than voice and timing: the contrast is between strong and weak stops - linguists call them fortis and lenis. In English, p t ch k are fortis, and b d j g are lenis. The distinction determines voice, but not in a straightforward manner.

The situation in English is described on the English page, but here's a summary. Fortis stops are normally aspirated, but in several contexts, they can become tenuis. Lenis stops are normally unvoiced next to unvoiced sounds or pauses, and voiced otherwise. Sometimes, that results in a merger between fortis and lenis: the distinction is lost, as in English discussed versus disgust. In other contexts, the distinction is preserved by interrupting the fortis stop in some way: by holding it unreleased, by reinforcing or even replacing it with a glottal stop, and/or by clipping the preceding vowel.

A pedantic digression: we normally refer to these unvoiced lenis stops as devoiced, as if the voiced allophones were the "real" lenis stops (even though the unvoiced are more common). "Devoiced" also leaves room for partial voicing: when initial, these stops may start voicing before the release (negative VOT), and when final, they may end voicing after the closure. But those nuances are barely perceptible by human ears, if at all, so we write them with unvoiced letters.

In Musa, we write fortis and lenis stops with their phonetic voice, in other words, we write them like they sound. We write aspirated fortis stops with aspirated letters, voiced lenis stops with voiced letters, unaspirated fortis stops and unvoiced lenis stops with tenuis letters, and held stops with held letters.

For example, consider the words boardwalk and warthog. The b in boardwalk is unvoiced, because it's next to a pause (the beginning of the word). The g in warthog is unvoiced, too - it's next to the pause at the end of the word. The k of boardwalk and the t of warthog are unreleased, and the preceding vowels are clipped. In some dialects, the stops might even be omitted, pronounced with creaky voice, or replaced by a glottal stop. And the d of boardwalk is voiced: it's surrounded by voiced sounds. Another pair of examples: the p of port is aspirated, but the p of sport is tenuis, and both end in a held t.

Implosive Consonants

(Voiced) implosives are written using voiced letters inverted to form an open box :

(Voiceless implosives use an orthophonic manner.)

Ejective Consonants

Ejectives are written using unvoiced letters inverted to point downwards:

For example, here are the nine affricates of Tlingit:

Fricatives, including sibilants, can also be ejective:

Aspirated fricatives are very rare; when they occur, we write them with the same ejective letters.

Applosive Stops

A normal plosive stop involves two events: the first is the stop itself, when the airflow is interrupted, and the second is the release, when it resumes again. The distinction between voiced, tenuis, and aspirated stops boils down to when the voicing is turned off. In a voiced stop, it's never turned off. In a tenuis stop, it's turned off at closure and back on at (or close to) release. In an aspirated stop, it isn't turned back on until noticeably after the release.

But some languages, including English, use stops that are not released. Of course, it's not the case that the airflow is never released! The airflow is eventually released, one way or another, the raised air pressure in the oral cavity is dissipated, and we go on with our lives, breathing. But it's not released as part of the stop event. Because of this nuance, the IPA diacritic is called "No Audible Release". But even that isn't really a good name, since the release may be audible; it's just part of the following stop, or part of a following nasal or lateral, or the overpressure is released through action of the glottis or even the lungs. And I would get tired of referring to these stops as "not audibly released"!

The academic word for these stops is "applosive", but I'll sometimes refer to them as "held". Musa has a set of letters for applosive stops:

There are no letters for applosive affricates, because affricates have fricative releases. And there are no letters for voiced applosive stops, since when you hold a voiced stop, it sounds just like a applosive unvoiced stop. That explains why a language like Thai can have three series of initial stops - voiced, tenuis, and aspirated - but only one series of final stops: applosive.

In English, we hold stops that occur after the vowel in several cases. Typically, we hold final fortis stops p t k to distinguish them from the lenis stops b d g, since the latter are devoiced before a pause or a voiceless sound. This also helps us distinguish applosive final consonants from aspirated initial consonants, as in the distinction between great ape and gray tape . We don't get the same help with lenis stops: cold rain sounds just like coal drain (except for the affrication of the d before r).

We also hold stops before other stops, as in act or apt, or even abdomen or subterfuge (which sound like apdomen and supterfuge would). A applosive stop helps us identify the end of a syllable, as in the difference between rat̚shit and ratchet, or between night-rate and nitrate.

A note about the phonology: Musa is agnostic on the question of whether unreleased stops in the coda are allophones of any stops that appear in the onset, in a given language - we just don't care. Musa also uses these same letters whether or not the oral stop is reinforced by a glottal stop, as in Chinese and Thai, or not, as in Vietnamese or Korean.

Holding of Affricates

Consider the two words cats and catsit . In the first, the t is released by the s, while in the second, the t is applosive, just like in the word cat , and the s starts a new syllable. So why don't we write affricates with applosive tops?

To explain that, we refer to a rule of thumb: when an affricate is in the syllable onset, we use the voicing of the plosive. That's why the ch of cheese is aspirated. But when the affricate is in the syllable coda, we use the voicing of the fricative. That's why the dj of hedge is voiced, not tenuis. And when the affricate is ambisyllabic - between and part of two syllables - we don't need to show that the plosive is applosive - that's always true of affricates. So the written top reflects the voicing of the onset of the second syllable. That's why the ch of ratchet has the same tenuis voicing as the ck of racket . In contrast, the t of ratshit is applosive, since it's not an affricate: the sh is in the next syllable.

Putting it all together

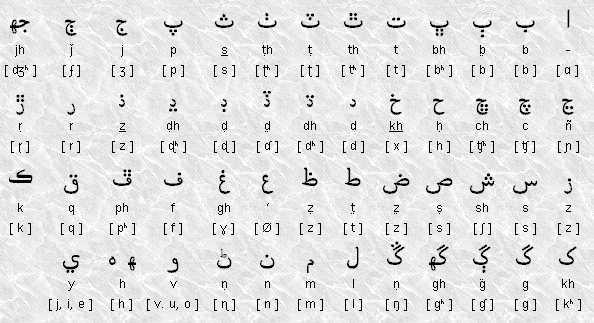

To show you how these letters work in practice, let's consider the example of Sindhi, an Indo-Aryan language most of whose 35 million speakers live in the Pakistani province of Sindh and neighboring India. Sindhi has 46 distinct consonants, so it's a particularly complicated example. It's currently written in both the Arabic abjad and the Devanagari abugida (the script in which Hindi is also written), both of which have had to be modified for Sindhi.

In Sindhi, as in most Indo-Aryan languages, there are five articulatory positions: labial, dental, retroflex, palatal and velar. But I chose Sindhi as an example because it also has five different plosives, differing in phonation, for each of the five articulatory positions mentioned above. The top line of the following illustration shows all five of the labial plosives : aspirated, unvoiced, breathy, voiced and implosive. The bottom line shows all eight nasals.

It's complicated, but remember that Sindhi already has different letters for all these sounds in both the Arabic and Devanagari scripts, and they're much less straightforward than the Musa versions - here's the Arabic:

Compare the letters for the last row with the Musa, above. Which would you rather learn, and write?

In fact, the province of Sindh has one of the lowest literacy rates in South Asia - less than 60%. Only neighboring Balochistan's is lower. On the other side is Gujarat, with 85% literacy, written in an Indian abugida. Perhaps the scripts matter more than we usually think.

Clicks

Clicks are produced by trapping air between two closures and lowering the tongue to produce a relative vacuum - in other words, by sucking (with your mouth, not your lungs). This vacuum is then released by opening the forward closure while the rear one is used to modify the air rushing by.

The rear closure - called the manner - is always velar, and can vary in phonation across the entire range described above, plus nasal and even prenasal. The forward closure - called the release - can be bilabial, dental, alveolar (retroflex, post-alveolar, apical, or sub-apical), palatal (palato-alveolar, laminal) or lateral (alveolar, dental, or palatal). The click can also begin a consonant cluster, for instance followed by a glottal stop or even an ejective.

Click consonants are most common in the Khoisan languages of southern Africa, some of which have over 50 different clicks, but their use has spread to neighboring Bantu languages, for example Zulu and Xhosa, the two most widely-spoken non-European languages in South Africa. We'll use them as an example of how Musa handles clicks.

Clicks are written in Musa as a digraph : the first letter indicates the manner, and the second indicates the release. The manner is always written with a velar letter. Here are some examples :

For the releases, Musa uses a square top :

Musa also has a letter for the rare velar back-release click release, in which it is the rear closure that is released. We don't yet have a letter for the very rare rertoflex click, but Muru is available, if it should ever be needed.

To illustrate the Musa click notation in practice, here are the 15 clicks from Xhosa and Zulu, along with their traditional Roman orthography :

Recap

Here's the chart from the last page, with clicks, ejectives, implosives, aspirated, breathy and murmured letters added, and some more letters from the groups above. I also included some suffixes you haven't met yet.

That's a total of 341 letters, and there are still others that could be constructed. But they're all just combinations of the basic shapes you saw on the first page - not that hard! Each language uses only the ones it needs; English needs only 50 letters. But if you want to write Sindhi or Xhosa, Musa has the letters you need.

| < More Positions | Suffixes > |

| © 2002-2025 The Musa Academy | musa@musa.bet | 02may25 |