Why Musa for Japanese?

Why Musa for Japanese?

Why is our writing so complicated? How does that help us to communicate?

榲Imagine that you are strolling through the basement of Takashimaya, and you see some fruit that you don't recognize. It looks kind of like a pear, but harder. Fortunately, the name of this fruit is on the display. Unfortunately, you don't recognize this kanji.

榲Imagine that you are strolling through the basement of Takashimaya, and you see some fruit that you don't recognize. It looks kind of like a pear, but harder. Fortunately, the name of this fruit is on the display. Unfortunately, you don't recognize this kanji.

Maybe you can guess that it's the name of a plant, since it has the 木 tree radical. But you can already see that it's a plant, so that doesn't help much. And maybe you can guess that it's pronounced un or on, since you know the 溫 variant of 温. (Actually, it has onyomi of otsu, ochi, or un, and kunyomi of sugi.) People sometimes say that the kanji tell us both meaning and pronunciation, but that's only true if you recognize them! If not, the kanji tells you very little.

The English name of this fruit is quince. The French call it coing, the Spanish call it membrillo, the Germans call it Quitte, and we Japanese call it marumero, from Portuguese marmelo.

The English name of this fruit is quince. The French call it coing, the Spanish call it membrillo, the Germans call it Quitte, and we Japanese call it marumero, from Portuguese marmelo.

Many Europeans who don't recognize the fruit will nonetheless recognize the name of the fruit, since they're familiar with products made from this fruit, like quince paste and quince jelly. Now they can see what the fruit looks like!

And of course they can pronounce the names without hesitation, even if they've never seen them before. That's because their alphabet spells the sound, just like hiragana, katakana, and romaji.

So why don't we just write マルメロ in katakana? That's what we do, and it works fine! So how does the kanji help us here?

麒麟On the landing page, you saw an ad for Kirin beer, but the name Kirin was written in rōmaji. Here it is in kanji.

麒麟On the landing page, you saw an ad for Kirin beer, but the name Kirin was written in rōmaji. Here it is in kanji.

麒麟The beer is named after a mythical animal, kind of a mix between a dragon and a deer, but with only one horn. Here's the kanji for that animal.

麒麟This animal also gave its name to the giraffe, the African animal with a long neck. Here's the kanji for giraffe.

麒麟This animal also gave its name to the giraffe, the African animal with a long neck. Here's the kanji for giraffe.

See the difference? I don't either.

Kanji is supposed to help us distinguish different meanings, but here, all these different meanings use the same kanji. In fact, most kanji have multiple meanings. Since the function of kanji is to indicate the meaning, it's not doing a good job in these cases. So how does the kanji help us here?

Now imagine that you work with a woman named Sachiko, and you have to leave her a note about something. So you write the note, put it in an envelope, and write her name on the envelope. But what do you write: 幸子 or 早智子 or 沙智子 or 佐知子 or 佐智子? You don't know which is correct.

Now imagine that you work with a woman named Sachiko, and you have to leave her a note about something. So you write the note, put it in an envelope, and write her name on the envelope. But what do you write: 幸子 or 早智子 or 沙智子 or 佐知子 or 佐智子? You don't know which is correct.

Why don't you just write さちこ? That's what you do, and it works fine! She finds the note, and there's no problem. So how does the kanji help us here?

Sometimes, kanji helps us distinguish between words that sound alike. But often, kanji introduces more problems than it solves. Since each kanji has so many different readings, you have to figure out which one the writer means. But the writer already knew which one he meant - why didn't he just write that?

It's as if you're playing a game of Pictionary: he thinks of a word, then draws a picture, and you have to guess what word he means. Why don't we stop playing games and just write the word?

But if we don't write with kanji, how will we distinguish between words that sound alike? What if someone writes こうしょう? What do they mean?

-

考証 examination

交渉 negotiation

公証 notarization

公称 nominal

高尚 noble

校章 school emblem

口承 oral tradition

Well, what happens if someone says koushou out loud? Can we understand them? Of course, because we speak Japanese, and we understand the words, even if they sound alike.

Most languages have many words that sound alike. English has very common ones like there their they're or to too two, and less common ones like praise prays preys or meat meet mete. In French, je l'ai fait cent fois and je les fais sans foi are entire sentences that sound alike. Chinese has the famous story of 施氏食獅史 The Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den, in which every word in the story is pronounced shi! And yet we manage to communicate. So writing the sound alone, with no meaning, isn't a problem.

If you don't believe me, try this little experiment. Ask your friend to read a written sentence or two aloud to you, and see if you can understand him. If you can, then you've proven that we don't need kanji!

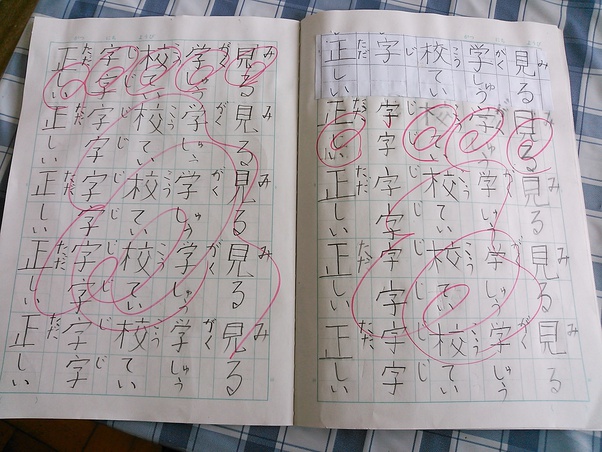

And the kanji are not easy to learn! Between Jōyō kanji and Jinmeiyō kanji, we have to learn about 3000 kanji, each with stroke order, multiple readings, and multiple meanings. That's 50-100 times more work than learning Musa, rōmaji, or kana! There are a lot of other things we could be learning, instead of wasting our time learning Chinese characters.

So why don't we just write in kana? An organization called the Kanamojikai has been promoting that idea since 1920.

Or we could write in romaji! That requires even fewer letters, and it makes clearer the relationship between マミムメモ: they all share the same consonant, even though the kana don't look alike. In fact, this has been proposed many times since the Meiji restoration, and is still being discussed.

But now there is an even better alternative: a new alphabet called Musa . Musa has several advantages: it has all the letters we need, so tsu chi shi don't need digraphs, and yō-on are written with one kana. The letters are featural, so letters that sound alike will look alike, and that makes them easy to learn. And the Musa alphabet is shared among many languages, so we can read foreign words and names, and learn foreign languages. The next page will explain how to write Japanese in Musakana.

Musa is a good way to write everyday Japanese, but it's a great way to write Japanese pronunciation. In Japanese, we use hiragana as furigana to indicate the reading of kanji, but hiragana doesn't show separations between words, pitch accent, or allophones (see below). Even romaji doesn't show the last two! But Musa does, so it's a great way to spell out the correct pronunciation of Japanese words and phrases, for students (foreign or Japanese), in dictionaries (print or online), and to talk about pronunciation.

But we can still use kanji to distinguish the meanings of sentences that sound alike:

| 私は生きます! | 私生 |

|---|---|

| 私は行きます! | 私行 |

When we write Japanese in Musa, we use Musakana to spell the sounds - all of them, including the reading of the kanji - and we can use Tomokanji to indicate the meaning, if we want. There are even fonts with Tomokana - little furigana above the Musakana for people who are still learning Musa.

| 榲 | | | | |

When we write Japanese in Musa, we write it more carefully than we do now. We write spaces between words, and we write the accent if we want. We also write the allophones, the changes in sound that we make when we speak. For example, we write the hatsuon and the sokuon as they are pronounced, and we write が as ga at the beginning of a word, and as nga otherwise, just like we say it. But you don't have to change the way you type! Just type the same way you do now - but with spaces between words instead of the Enter key - and the composer will spell out the kanji and the allophones. The next page will explain how it works.

Why don't we just spell the same way we do now, indicating which mora we mean without worrying about the correct pronunciation? We all know - consciously or not - that ち is pronounced chi, not ti, and that the particle が is pronounced nga, not ga. So why should we show that in our writing? We're used to this old way of spelling.

It's true that it takes a little getting used to before we learn to write phonetically, but it offers many benefits. Of course it makes it easier for us to learn foreign languages, and for foreigners to learn Japanese. But it also makes it easier for us to learn to write Japanese, since that's what we hear and speak. People sometimes say that they can't hear the difference between si and shi, or hu and fu, but of course they can - that's how they learned to pronounce them correctly! We have many gairaigo with f, like ファイト faito, and we don't pronounce them with h. And most of these allophones have standard extended katakana: hu ホゥ, tu トゥ, ti ティ, si スィ, zi ズィ, di ディ, du ドゥ.

So these allophones are something that children have to learn. They have to learn that tu is pronouned tsu - it's not natural. And of course that's true of every language: children have to learn the phonology, the phonemes. And the current Japanese writing, like most writing, writes phonemes. But Musa writes the sounds that we actually speak and hear. And that's easier!

We'll talk more about this on the next page.

| Musa for Japanese |

| © 2002-2025 The Musa Academy | musa@musa.bet | 10sep23 |